The Blog addresses…..

The Blog addresses any issues, which relate to the different ways of doing or researching HCI and in particular to the approaches and frameworks, proposed here. It will also be used to introduce relevant feedback to the site and to extend both the approaches and the frameworks, as and if required.

1. 29 February 2016 – User Requirements and Design Problems – Same or Different?

I am often asked ‘What is the difference between ‘user requirements’ and ‘design problems’? I need to pay my dues on this one. The Craft design research exemplar, presented here, includes only user requirements. The Engineering exemplar includes both. No-where is the difference explained.

User Requirements and Design problems – Same or Different?

2. 4 March 2016 – HCI Design Research and HCI Design Practice – What are Their Relations?

I have always argued for the strongest possible relations between HCI research and HCI practice. Here, I make some suggestions as to what those relations might be.

HCI Design Research and HCI Design Practice – What are Their Relations?

3. 7 March 2016 – Old Papers Never Die, They Only Fade Away……?

I often wonder, if old research papers have anything to say to us now, given the radical changes in information technology? Here are some comments on a joint paper I wrote some 35 years ago with John Morton, Phil Barnard and Nick Hammond entitled: Interacting with the Computer: a Framework

Old Papers Never Die, They Only Fade Away…..

4. 12 March 2016 – HCI as Art?

HCI as Art has the problem of conceptualising the work of art itself (the application) and the experience of the person, engaging with the work of art (the user). There is no general consensus about how to conceptualise either. However, I was lucky enough to come across an interesting example of the latter.

5. 3 April 2016 – From MSc Student to UCLIC Director – Some Reflections by Yvonne Rogers

Yvonne Rogers was a member of the MSc class of 1982/83. She was appointed Director of UCLIC in 2011. As a result, her MSc Reflections take on a wider and more general significance. For that reason, they are included here. The reflections are prompted by a set of standard headings. For other MSc student reflections – see elsewhere on this site.

From MSc Student to UCLIC Director – Some Reflections by Yvonne Rogers

6. 1 May 2016 – Is It Important to Distinguish ‘Hard’ from ‘Soft’ Design Problems.

‘Hard’ and ‘soft’ are used with respect to problems in general. The terms have also been used in HCI research to describe design problems, notably by Dowell and Long (1989). The comprehensiveness of their address of the differences warrants inclusion here, as the basis for arguing for their importance. Additional comments clarify issues, which arise in the application of the concepts to approaches and frameworks for HCI research.

Is It Important to Distinguish ‘Hard’ from ‘Soft’ Design Problems?

7. 25 May 2016 – HCI design frameworks are intended to support research, Can they also be used to support design practice? Peter Timmer suggests how an HCI Engineering framework can integrate HCI design practice with business services.

Introduction to Peter TimmerPeter Timmer was an MSc student of the class of 1989/90.

He worked at the EU from…..to…..as…..doing…..

After leaving the EU, he worked as…..doing…..

In the following paper (Timmer, 2010), Peter suggests how HCI design practice might be integrated with business services, like sales and marketing, better to relate to their associated practices of end-to-end and incremental sales and profit measurement for digital channels. To this end, he applies the Dowell and Long conception (1989 and 1998). Additional comments are intended to clarify issues of particular concern to HCI design research. Read more…..

Read MoreA Sketch of the ‘Conversion Funnel’. Can Cognitive Engineering Assist in its Design?

Peter Timmer

Bisant Ltd, 49 Clonmell Road, London, N17 6JY, England

John Long Comment 1

Cognitive Engineering, as used in the paper, can be considered co-extensive with HCI, as used here in the engineering approaches and frameworks.

End Comment 1

1. Abstract

The ‘white heat’ of commercial web design is increasingly around a business’ ‘conversion funnel’. Conversion funnels are the means by which the business services its customers, and such funnels are critical to the performance of the digital channel. In this paper, a sketch of commercial conversion funnel design practice is offered. A complex relationship is described, where web analytics increasingly helps the business measure performance. Dowell’s and Long’s conception (1998) [1], of the cognitive engineering design problem, is then used to suggest how the conversion funnel design process can be better structured, in a manner suitable for ‘design for performance’, and to address a business context of engineering that is at present ignored in commercial web site design.

Comment 2

The Dowell and Long conception (1998) appears here as the HCI research engineering framework.

End Comment 2

2. Introduction

Business services are delivered by ‘channels’, and channels are maintained by businesses for the purpose of contact and communication with consumers. Door‐to‐door sales representatives, direct mail catalogues, a branch network of shops, call centres, and digital (web sites) are all channels for managed contact with consumers. Channels all come with associated financial expenses to the business, at minimum, for maintenance of the channel.

Sales and Marketing functions within businesses drive product sales to consumers across all relevant channels, via techniques such as advertising campaigns. While it has always proved hard to measure the impact of a budgeted television commercial on sales within a particular channel, in the case of digital marketing this has proved to be easy. While a television advert rarely mentions a particular store, to the detriment of the product or brand being advertised, in the case of the digital channel, a banner advert can drive the prospective customer directly to a retail ecommerce site, and onwards into a purchasing journey.

One consequence of the directness of this relationship, between digital adverting and digital purchasing, is that all budgets can be measured within the business, and the expense of a banner advertising campaign, combined with the expenses of designing, building and maintaining a retail web site for the digital channel, can be weighed against the direct contribution to sales that the digital channel makes. Business expenses can be measured end‐to‐end, and incremental sales from the digital channel, and therefore profits, are known. The digital channel has a bright future because of this accountability between the marketing expense of the channel, and the channel’s marginal contribution to product sales.

Given that the design of ‘effective’ digital web sites has a bright future; this paper looks at how design for the digital channel might be structured within this context. In the first part of this paper, commercial practice is examined, in terms of the analysis tools available to the information architect who will design the core goal‐oriented journeys (education, consideration & fulfilment) and interactive experiences, such as navigation, that the web site needs to support. The concept of the ‘Conversion Funnel’ will be outlined in sketch form due to the size of the actual area of interest. In the second part of the paper, an attempt will be made to understand the sketched space in terms of a design problem of ‘cognitive engineering’ where ‘performance’ is the beginning and end of a design cycle; and the hypothesis testing of website analytics should be replaced with efforts to optimise web site performance through a more rigorous approach to the prescription of informed design specifications. The information architect will thereby become a cognitive engineer.

3. A Sketch of the conversion funnel

The concept of the conversion funnel has arisen from web site analytics, and speaks of a user’s journey across web pages that lead to a business service goal being achieved, such as a sale, appointment being booked, or completion of an application form. In these instances, such as clicking on a ‘Checkout’ button (in a retail context); the user is normally guided through a step‐wise process, to buy the product. This normally involves steps such as ‘Personal details’ (needed for shipping and logistics), Financial details (needed for billing and finance), Accept Terms and Conditions (needed by legal), ‘Opt‐in’ to future product marketing updates and offers, and so forth. Each of these sub‐sets of customer data is mandated by the business, for service delivery in the digital channel.

A statistical phenomena of such step‐wise journeys, is that you can’t have more users at step 3 than were at step 1. Through the conversion funnel you can only lose users, and subsequent service opportunities. Web site analytics enable each page on the user’s journey to receive a unique ‘tag’ that enables user clicks to be tracked. All buttons and controls on all pages can be tagged, so where there is more than one way to the next step, individual buttons on the page can be assessed for success, at guiding the user’s journey. Web analytics’ claim is that this tagging and analysis process informs web site ‘optimisation’, by generating statistical aggregations of user behaviour on a set of tagged pages.

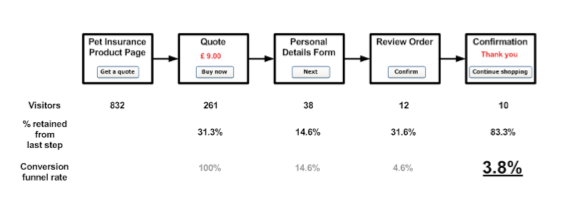

If we take an example, Figure 1 shows illustrative conversion funnel data for a ‘quote and buy’ service, offered by a business in the digital channel. A five page journey is of interest, and while all pages are tagged, a conversion funnel has been set‐up for a user journey from offering a quotation, to purchase confirmation – the last four pages of the journey.

Figure 1 tells the following story.

On a business web site, a Pet Insurance product is described, and offered for purchase in the digital channel. Product information is displayed to the user on a single page, the ‘Pet Insurance Product Page’, shown in Figure 1 top left. Analytics data reveals that on a single day, this product page had 832 unique visitors. The page holds an important primary Call to Action, ’Get a quote’.

When the user clicks the ‘Get a quote’ button, on the product page, they are taken to a ‘Quote’ page. Accurate quotations require a number of pieces of information to be elicited from the prospective customer, so on the Quote page radio buttons and drop‐down choice controls enable the pet (to be insured) to be described. A dynamic quote is thereby generated within the page, based on the user’s actions. Here, a quote of £9.00 results, and once a well‐formed quotation is generated and displayed, a ‘Buy now’ button is offered to the user. Analytics show 261 users, of the 832 users who visited the product page, progressed to see the Quote page. That is 31.3% retention of interest in the product. This group, of 261 users who click on the ‘Get a Quote’ button, may be considered by the business to be a target group of ‘warm prospects’, users judged as having a genuine interested in the product, and are ready to act within the digital channel. Of the 571 visitors to the product page that didn’t seek a quote, some may have been conducting research, and then progressed an order via a Call Centre channel, or approached a shop branch or broker channel. The digital channel may still be serving important user needs even when action within the channel is not evident.

If the prospective customer then clicks the ‘Buy now’ button on the Quote page, having considered the quote, they are taken to a ‘Personal details’ form, where contact and financial details are captured. A ‘Next’ button then progresses the user onto a ‘Review Order’ page, and a ‘Confirm’ button will generate an Order Confirmation page. In theory, everybody who sees the Order Confirmation page is a customer of the business, as they have bought the product via the digital channel. The Order Confirmation page is therefore the end of a transaction process, and cannot be found and visited via the navigation, or passed as a URL within an email.

Analytics data show, across these pages, a gradual drop‐off in visitor numbers as prospective customers ‘bounce’ out of this journey to purchase the product, maybe via bookmarks or by closing the window. It can be seen that only 10 users saw the Confirmation page on the day in question, 10 prospective customers became actual customers of the business. Tabulated below the analytics data for page visits are percentage statistics that reflect the volume of visitors retained by the digital channel, from preceding steps. Only 14.6% percent of people who sought a quote, elected to then ‘Buy now’, and of this elite group, two thirds were then lost during form filling.

Finally, a conversion funnel has been set up from the Quote page through to the Confirmation page. If the 261 visitors to the ‘Quote’ page are considered a target group for purchasing (the warm prospects), and only 10 of that group of prospective customers actually became customers (the ones that saw the Confirmation page), the businesses digital channel has a 3.8% conversion rate for this product.

4. Information architecture and the conversion funnel sketch

Now, information architects design the pages that are reflected in such statistical analyses of the web site, and web site analytics reflect a limited ‘glimpse’ of a web site design’s ‘performance’. Where a business has sales targets for the digital channel, it is possible that the current volume level of 10 product sales per day is insufficient to justify the expense of the channel, and uplift is needed to 20 sales per day, for the achievement of business benefit in offering the channel to prospective customers. In this case, of the 261 visitors to the Quote page, changes need to be made to the digital channel (web site) and/or sales process, so that a 7.6% conversion rate is attained (20 confirmation pages are seen from the 261 who saw the Quote page). This may be possible without changing the website significantly. A ‘5% off’ offer could be given to the user. Alternatively, theories may be created about how the Quote page could be improved, to get more people through to click ‘Buy now’ and start filling the Personal Details Form. Instructional text may be insufficient to reassure the user how easy the process will be, or ‘Buy now’ buttons may be out of sight and require scrolling. The business, in conjunction with the information architect, may thereby seek to redesign parts of the site to achieve improved conversion rates and sales volume uplift. Alternatively, the business, in conjunction with digital marketers, may place an increasing number of banner adverts on partner sites, to drive twice the volume of users to the product page, and thereby mine the existing statistical patterns through the conversion funnel to reach the same end result, 20 target sales for the channel. This paper is concerned with the former.

Drawing on conversion funnel data, the web site is thereby changed, maybe with clearer instructional text and two ‘Buy now’ buttons, one at the top and one at the bottom of the page. The changed site is then measured, in a similar manner to the first design, and over time a comparative conversion funnel is generated. While a method of applied science would appear to be being employed, the difference between two (measured) digital experiences may be a great number of site alterations, each alteration reflecting a hypothesis, with many parties within the business generating hypotheses and requesting changes. If uplift is attained, it may be hard to know which alteration was most effective; but then all the business wants is uplift, not the practice of a purely scientific approach.

Comment 3

Both Science and Applied approaches to and frameworks for HCO research are proposed here.

End Comment 3

To compliment multiple design changes to pages, it is possible to conduct ‘split’ testing, or AB testing, on page elements such as button designs, labelling, font size, imagery and so forth. In this case, two buttons may be designed, one saying ‘Buy now’, and another saying ‘Join us’, and placed in the page in equal measure until a statistical difference in usage is detected. Then, one design may prevail as being more effective, and so testing single hypotheses can also be undertaken. An image of a sick animal may be more effective at driving people to ‘buy’ pet insurance than an image of a happy customer. The page ‘design specifications’ that support the conversion funnel can in this way be tweaked and thereby optimised to meet business goals. The cost of changing the digital channel’s user experience needs to be weighed against incremental gains, through better conversion rates.

Earlier, when the conversion funnel was sketched, the claim that web analytics can ‘optimise’ a web site was touched upon. Web site analytics does appear to support web site optimisation, but optimisation is about more than measuring aggregated and individual click paths. Optimisation has a second component that has been mentioned here, design specifications. Behind the aggregated statistics are designed pages that form the user’s experience. To optimise the pages, in line with business targets, design specifications are required, and specifically ‘designs for performance’. Designed changes need to attain targets, and address unnecessary user problems getting through the funnel. The user can at any point leave the funnel simply by clicking away on a bookmark. If the prospective customer is to be converted into a business customer in the digital channel, but are confused by what is being viewed during the purchasing journey, such confusions need to be removed from the design. A specification for a design solution is needed, to compliment the design problems uncovered by the web site analytics. Together, analytics and design specifications support web site optimisation.

Comment 5

The possible relationships between user requirements and design problems are addressed in the Blog 1 of 29 February 2016.

End Comment 5

5. Cognitive engineering and design problems

The above picture of commercial design practice takes in many individuals, disciplines and concerns; and so the design process needs guidance, in how to structure the way in which the root design problem of digital channel ‘performance’ is conceived, and thereby approached in the design process. In this regard, the paper asserts that the sketch provided, of the conversion funnel, can be best understood in terms of a design problem of cognitive engineering. A conception of cognitive engineering as ‘design for performance’ (Dowell & Long, 1998 [1]) will be used to re‐express the problem of conversion funnel design, in a manner suitable to the engineering context of ‘optimisation’ that exists around it, in all but name.

The digital channel to prospective customers is one channel of many, but all channels can be conceived of in terms of Ergonomics, in that all channels will involve to a greater or lesser extent, humans interacting with devices to perform effective work (Dowell & Long, 1989 [2]; Long, 1987 [3]). Where businesses offer common services across multiple channels, the humans in question (prospective customers) interact with functionally equivalent devices to perform the same ‘work’, such as product purchase. Web sites offer ‘electronic form’ devices to the user. Direct mail channels offer paper‐based form devices, pre‐paid envelope devices, and sometimes even pens. Via different channels a common range of products can be purchased. To the prospective customer, the work is the same – generating an order; but with different devices, levels of performance may widely differ.

Comment 6

The same ‘work’ would be expressed by the Engineering Framework, proposed here, as transforming a product from to unpurchased to purchased. Different channels offer different means by which the transformation can be brought about.

End Comment 6

Dowell and Long conceive of performance as having two inseparable components, ‘Task Quality’ and ‘User Costs’. Quality here refers to how well formed the order is, by interacting with the devices that the business offers (via the channel).

Comment 7

‘Task Quality’ would be expressed by the Engineering Framework, proposed here, as how well (that is, as desired) the unpurchased product is transformed to purchased – see also Comment 6.

End Comment 7.

The static and standardised images of a paper‐based catalogue may generate more returned products to a business than a web site that offers zooming, panning, and a library of product photographs from different angles. When the order is fulfilled, users of the digital channel may be more likely to be delighted with their purchase, than a user who was unable to determine aspects of the product until closer inspection was possible. The quality of the user’s work varies across channels. Associated with work of a given quality are costs to the user. These may be most simply conceived of as time and effort, or may be more refined and make reference to costs of mental and physical human behaviours (e.g. training), plus device costs such as load on a server of posting back information to that server, after every click. In our retail example, the time cost of waiting for the postal delivery of a paper‐based order form (back to the business in the direct mail channel) may be removed by using the digital channel’s electronic form. Going to a branch to buy the product may involve the prospective customer incurring greater costs (time, effort, financial), but generate the highest quality of work. There again, a lack of stock at a local branch may lead to the work being left undone when this channel is chosen, with other consequent costs to the user, of performing work of zero quality, such as frustration. When looking at digital channel performance, it is therefore helpful to look at performance in these terms, quality of work done at some cost.

In this retail example, the similar work undertaken across different channels may be abstractly conceived of as one whereby ‘ownership’ of an object or objects, is transferred from the seller to the buyer, along with the physical location or evidence of ownership.

Comment 8

This characterisation of work is consistent with that appearing in Comments 5 and 6.

End Comment 8

A lamp appears in your living room, or a policy number is sent to you via post. In each case, the prospective customer interacts with devices, provided by the seller, to ensure this work is performed effectively. Dowell & Long call the human interacting with the channel’s devices the ‘worksystem’. The worksystem incurs costs as its contribution to the expression of work performance.

Comment 9

Both humans and channel devices incur costs. See also earlier in the paper.

End Comment 9

Worksystem design for the digital channel needs to be similarly conceived. The product browsing experience needs to be simple and informative, the route to the checkout needs to be self evident, and product selection supported by devices such as ‘baskets’, with clear means of action (‘Add to Basket’ buttons) and action reversal (‘Remove’ buttons). A shopping checkout experience that looses 96% of customers that approach it, with something in their basket, thereby becomes a very interesting and commercially valuable design concern. Channel performance needs to be improved, but can that improvement be brought about by increasing the likelihood of higher quality work being done, at a lower cost of time and effort to the worksystem? It is suggested here that this is a helpful way to think about structuring the root design problem of the digital channel, performance. Generating uplift in the digital channel through redesign of web pages is a problem of cognitive engineering.

Dowell and Long’s conception mirrors the behaviours of worksystem, with an abstract place, entitled the ‘domain’ which is comprised of domain ‘objects’.

Comment 10

Domain objects are modelled in Dowell and Long and in the Engineering Framework, proposed here, as objects having both physical and abstract attributes and states.

End Comment 10

In retail domains, the objects may be modelled in a variety of ways; what is important to the conception is that each behaviour of the worksystem is understood in terms of progressing some desired transformation of a domain object on its way to a final state whereby the work is accomplished. In a retail domain, ownership of a domain object is transferred. One simple model of such a domain may be in terms of transforming ‘order’ objects from a state of ‘empty and unfulfillable’ (no object in a shopping basket) through to ‘valid and unfulfillable’ (something in the shopping basket that can be purchased), and then on through the conversion funnel to a domain object (target) state of ‘valid and fulfillable’ (all personal, financial, and logistical details known to pay for and deliver the object to the new owner in return for the cash value). Until ‘Terms and Conditions’ are accepted for example, a valid order is unfulfillable, as the prospective customer has not yet accepted the ‘conditions of business’, for scenarios such as theft in transit. Such business logic pervades the digital channel, and yet is not a necessary part of the ‘work’ carried out by worksystems in the branch (shop) channel, where responsibility for safe transport is undertaken by the consumer once they have left the shop, with a well manufactured bag supplied by the business. The conception of a cognitive engineering design problem therefore ties worksystem behaviour into a view of how that behaviour is transforming the domain object into its target state – accomplishing effective work. Task quality is used to measure the work done in the domain, and so the measurement of worksystem performance has a second element, inseparable from worksystem costs. Costs cannot be truly understood unless we know what work they were incurred ‘doing’.

Comment 10

And indeed, how well that work is done – whether as desired or not. See the frameworks proposed here.

End Comment 10

Engineering ‘design problems’ then arise when desired levels of worksystem performance are poorly aligned (do not match) with levels of cost and quality desired by the business (digital channel provider). At such a point, after desired performance is known and expressed, and actual performance known and expressed, and poor alignment is thereby expressible, cognitive engineering design processes can be undertaken, as they can be grounded in worksystem performance measurement.

The cognitive engineering design processes that are broadly employed when solving performance‐ oriented design problems are ‘diagnosis’ and ‘prescription’. The business, at minimum, will have expectations that a digital channel will generate, across all its ‘valid and fulfillable’ orders, a level of profit. If this level of profit is being attained, but the business has unusually high levels of returned goods, and subsequent re‐funds, a place to start diagnosis might be on the ‘browse’ and ‘add to basket’ experience. Are product sizes well displayed? Do prospective customers know what they are adding to the basket? Alternatively, profit may be visible in the value of total order objects that progress from ‘empty and unfulfillable’ to ‘valid and unfulfillable’, but enormous numbers of prospective orders may be abandoned in the Conversion Funnel, maybe at the Terms and Conditions step. Diagnosis in this case may start by looking at the Worksystem at this point in the retail experience.

The cognitive engineering process of diagnosis will draw on as much Business Intelligence data as is available, about worksystem behaviour, to establish a plausible theory about why the performance data indicates a design problem exists. Prescription, then involves specifying a design solution, one that will alter the performance data, bring about ‘uplift’, and align the businesses desired level of performance with actual levels. Cognitive engineering, by separating worksystem from domain, modelling worksystem behaviours as separate from domain object transformations, and measuring worksystem costs alongside work quality, offers digital channel designers a valuable means of structuring how the root design problem of performance is conceived (Dowell & Long, 1998) [1].

6. Performance measurement

Dowell & Long’s conception of the cognitive engineering design problem is not alone, in trying to outline basic fundamental components that make up an engineering discipline of ‘cognitive design’. It has however been chosen, because of its emphasis, less on ‘cognitive behaviour’ leading the design process, as much as deficiency in ‘performance’, and then re‐specifying the worksystem, and most importantly the human ‘cognitive’ component (that leads to the creation of business ‘customers’), as a means to address a design solution to the problem. The user’s cognition drives their action, which thereby progresses them through the conversion funnel. A button may be rendered larger, and brighter, to capture a customer’s mental process of ‘attention’ (Long & Baddeley, 1984 [4]), a clear table may support ‘reasoning’ about a choice (Buckley & Long, 1990 [5]), and thereby encourage the desired user ‘click’ (behaviour), that will improve performance data towards the businesses desired performance levels, and turn problem into solution (alignment).

By attributing a measurement of cost and quality to an expression of performance, and the concepts of ‘desired’ and ‘actual’ levels of performance to assist in the framing of a ‘design problem’, cognitive engineers have a number of places to start the diagnosis process.

Firstly, the business needs to be able to express desired performance. This will likely be in aggregate terms, and largely reference task quality, especially the number of occasions the worksystem generated ‘valid and fulfillable’ orders, and the total value of those orders, against some measurement of cost (expense), in supporting the digital channel to the consumer. Performance is also likely to make reference to the missed opportunity in terms of low task quality and high user costs. Orders abandoned in the conversion funnel (‘work’ left undone in the domain), time to progress through the conversion funnel at each step, complaints and customer satisfaction ratings (worksystem costs). It is in measuring actual performance via such criteria that web site analytics, and wider Business Intelligence, provides the cognitive engineer with a valuable toolset for performance measurement and thereby design problem diagnosis.

While the engineering approach relies on the business to express ‘desired performance’, once this is expressed, means are required for measuring the actual performance, and so by: tagging pages across the site; modelling user journeys and paths across the site; measuring the time spent on each page; and comparing this to the value of the basket at each step; measurements of actual performance (of individual prospective customers) can be aggregated into summary statistics. These summary statistics are models of performance that support diagnosis, diagnosis of points in the journey where performance starts to deteriorate, against the performance which is desired. Diagnosis may start from pages where performance deteriorated beyond repair, instances where prospective customers were lost from the funnel (and wider site) completely – they ‘bounced’ away, or pages where time spent before advancement appeared unusually long, as hesitancy and uncertainty sets in. Web site analytics can provide granular and aggregated data to support the cognitive engineer in diagnosis, and reasoning about why the performance data are as measured, and indicative of the origins of a plausible design problem; the design problem under consideration.

In contrast to scientific hypotheses, that are part of a scientific method to generate scientific knowledge that supports better ‘explanation and prediction’; cognitive engineering needs to develop a set of diagnoses that when addressed during the cognitive engineering process of ‘prescription’ (specification), will improve and align the Worksystem’s performance data so that it better matches the businesses desired level of performance. If uplift is not possible, the digital channel may disappear as a candidate user experience choice for prospective customers, when interacting with the business.

Diagnosis therefore needs to go beyond an approach of applied science, and instead to look at the user’s journey to a point where performance deteriorates, as well as the page where deterioration is most marked. Theories need to be generated by the cognitive engineer that draw upon all the disciplines that support cognitive design (attention, reasoning, vision), to explain the performance (design) problem. The abandonment of a basket at the page before confirmation may have little to do with a problem with the order summary page itself. Quite the opposite is possible when the user’s journey is examined. The order summary page may reveal the true transportation expense of the ‘valid and fulfillable’ order, expenses that if known earlier would have resulted in fewer prospective customers abandoning their order at such a late stage. Diagnoses need to consider the customer’s journey, and the mental events that the pages support, such as ‘true order cost realisation’. Prescriptions will then follow, in the form of design specifications that address the diagnosis and thereby solve the design problem.

7. The Conversion Funnel design revisited

Business Intelligence for the digital channel is taking many forms, and introducing many new issues around not only consumer privacy, but also around the limits of what can be inferred about consumers from their digital footprints (Baker, 2008 [6]). As many interests compete for influence over the user experience through the conversion funnel, a framework is required to structure the design process so that interests are weighted appropriately. The business owns the channel to its prospective customers, and once it has decided on the key objectives for that channel, it will inevitably set performance targets for the channel. Technologies are evolving to subsequently service the businesses interest in digital channel performance measurement, and it is important to understand the strengths and limitations of the ‘glimpse’ of customer cognition that statistical models provide, something Guy Debord would call ‘the spectacle’, and how we design based on these impoverished representations of the consumer’s reality (Debord, 1967 [7]). In this paper, Dowell & Long’s (1998) conception of the cognitive engineering design problem has been used to bring some order to these competing interests; and better understand what contribution different parties are making to the primary business objective of digital channel performance. Click paths and conversion rates represent aggregations of humans interacting with computers to perform work, and their greatest contribution to the primary business objective is to measure performance, and provide the cognitive engineer with diagnostic inputs, and evidence a re‐designed conversion funnel really is the design solution the business is looking for. To compliment measures of quality and cost, the cognitive engineer needs to tie a digital experience in the digital channel (prospective customers interacting with digital devices), to a domain where work is done, and business targets are attained. This design process will then draw upon models of cognition. Cognitive ‘engineering’ of a design solution is thereby grounded in performance, at the start (diagnosis) and end (prescription) of each design cycle. It is because this is increasingly how the digital channel is being designed, that Dowell & Long’s conception has been chosen. Cognitive engineering in practice, is about designing devices that support cognition, which supports action, which transforms domain objects to accomplish work, of a quality and at a cost. The interests of the cognitive engineer and the business are thereby aligned, by a common interest in channel performance.

8. References

[1] Dowell, J., Long, J. B., 1998. Conception of the cognitive engineering design problem. Ergonomics 41 (2), 126‐139.[2] Dowell, J., Long, J. B., 1989. Towards a conception of an engineering discipline of human factors. Ergonomics, 32 (11), 1513‐1535.

[3] Long, J.B., 1987. Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction. In: Warr, P., (Ed.) Psychology at Work. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

[4] Long, J. B., Baddeley, A., (Eds.). 1984. Attention and Performance IX (International Symposium on Attention and Performance). Lawrence Erlbaum.

[5] Buckley, P., Long, J. B., 1990. Using videotext for shopping – a qualitative analysis. Behaviour & Information Technology, 9 ( 9), 47‐61.

[6] Baker, S., 2008. The Numerati. Jonathan Cape, London. [7] Debord, G., 2004. Society of the Spectacle. Rebel Press.

[7] Debord, G., 2004. Society of the Spectacle. Rebel Press

8. 10 June 2016 – Smell-enhanced human-computer interaction ? Surely not! Marianna Obrist, however, does not agree.

Introduction to Marianna ObristI first met Marianna Obrist, following a seminar, which she presented at UCLIC in May, 2014. The seminar was entitled: Multi-Sensory Experiences: How we Experience the World and How we design Technology. I much enjoyed Marianna’s seminar, which together with a chat afterwards revealed common interests in understanding human experience/behaviour and its relationship to design. My PhD thesis involved multi-dimensional vision and audition. However, research on the multi-sensory experiences of touch, taste and smell was new to me.

Marianna and I subsequently exchanged e-mails about the research and in particular concerning the way forward and the issues raised. I offered to review two papers reporting this research for the HCI Engineering website – an offer, which Marianna accepted, as follows.

‘I am particularly interested in the impact of the research on technology design, as it was not only a question, raised following my UCLIC seminar; but also on other occasions. However, I still believe that we need to establish the foundation and vocabulary for the senses of touch, taste and smell. I would like, then, for the review to include both the understanding of the experience of these senses and the application of that knowledge to the design of technology involving HCI. Both the future direction of the research should be considered, including the issues raised.’

In the following paper, Obrist et al (2014) argue that technologies for capturing and generating smell are emerging and our ability to engineer such technologies and use them in HCI is rapidly developing. They investigated the experience of smell by means of an on-line questionnaire, which produced 10 categories of smell experience. The categories, in turn, were explored for their design implications. The research is considered to contribute to the development of smell-enhanced HCI. Comments are based on the original review of the paper and are intended to clarify issues of particular concern to HCI design research. Read more…..

Read More…..Opportunities for Odor:

Experiences with Smell and Implications for Technology

Marianna Obrist1,2, Alexandre N. Tuch3,4, Kasper Hornbæk4

m.obrist@sussex.ac.uk | a.tuch@unibas.ch | kash@diku.dk

1Culture Lab, School of Computing Science Newcastle University, UK

2School of Engineering and Informatics University of Sussex, UK

3Department of Psychology, University of Basel, CH

4Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen, DK

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full

citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others

than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise,

or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific

permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from Permissions@acm.org.

CHI 2014, April 26 – May 01 2014, Toronto, ON, Canada

Copyright 2014 ACM 978-1-4503-2473-1/14/04…$15.00.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557008

ABSTRACT

Technologies for capturing and generating smell are emerging, and our ability to engineer such technologies and use them in HCI is rapidly developing. Our understanding of how these technologies match the experiences with smell that people have or want to have is surprisingly limited. We therefore investigated the experience of smell and the emotions that accompany it. We collected stories from 439 participants who described personally memorable smell experiences in an online questionnaire. Based on the stories we developed 10 categories of smell experience. We explored the implications of the categories for smell-enhanced technology design by (a) probing participants to envision technologies that match their smell story and (b) having HCI researchers brainstorm technologies using the categories as design stimuli. We discuss how our findings can benefit research on personal memories, momentary and first time experiences, and wellbeing.

Author Keywords

Smell; smell experiences; odor; olfaction; user experience; smell-enhanced technology; narratives; smell stories; crowdsourcing; design brainstorming; designing for smell.

ACM Classification Keywords

H.5.2 Information interfaces and presentation (e.g., HCI): Miscellaneous. General Terms

Experimentation, Human Factors, Design.

INTRODUCTION

Smell plays an important role for memories and emotions.

Compared to other modalities, memories evoked by smell

give stronger feelings of being brought back in time, are

more emotionally loaded, are experienced more vividly,

feel more pleasant, and are autobiographically older

(ranging back to childhood) [15,33]. Smell is incredibly

powerful in connecting humans to past events and

experiences.

John Long Comment 1

For all frameworks, there is a need to distinguish a/the smell (noun, that is, what is smelled) from to smell (verb, that is, the act or sensation of smelling). The title of the paper, in fact, does this by using the terms ‘odour’ and ‘smell’ and contrasting them with ‘smell experience’. Maybe odour could be used as the stimulus, which evokes the perception of smell(ing). There is also a need to distinguish the perception of smell from the memory of a smell perceived (in the past); but evoked by its present perception. Both need also to be related to ‘smell experience’.These differences are important and need to be made explicit for the support of design.

End Comment 1

Matsukura et al. [22] recently proposed the Smelling Screen, an olfactory display system that can distribute smells. Earlier work in HCI has proposed other systems that capture and generate smells. For example, Brewster et al. [5] developed a smell-based photo-tagging tool, and Bodnar et al. [4] showed smell to be a less disruptive notification mechanism than visual and auditory modalities.

Comment 2

Does ‘smell’ here imply modality (like visual and auditory) or is ‘smell’ what is perceived (and so what disrupts). See also Comment 1 for the need of making such distinction explicit and so, clear.

End Comment 2

Thus, smell technologies are already emerging. Our understanding of how these technologies match the experiences with smell that people have or want to have is surprisingly limited.

Comment 3

There is a need to clarify the use of ‘understanding’ here. Does it mean as used in everyday language or as used in science? The difference would determine which frame work is appropriate.

‘Understanding (smell) experience’ in everyday language, that is most generally, means to identify with or to recognise someone else’s experience, as in agreeing with a friend’s assertion, that ‘bitter beer is nasty because it smells’. This provides us all with ‘insights’ into our and others’ experiences (of smell). Is this the sort of understanding and insights sought here? If so, an analysis of the every day descriptors of smell experience, in terms of what can and cannot, be said about smell, might prove helpful (also to designers). If not, then further definition of the understanding and the insights implicated would prove prove useful.

End Comment 3

First, while technologies such as those mentioned above are often evaluated, the results mainly concern the perception of smell. The evaluations say little about the general potential of smell technologies for humans or their ability to generate particular experiences.

Comment 4

There is a need to clarify rather more the difference between the ‘perception’ and the ‘experience’ of smell(ing). See also Comments 1 and 2.

‘Experience’ is considered generally to be central to the concept of HCI as ‘User Experience’ (see Rogers, 2013). The strength of the concept lies in its inclusivity. Nothing concerning the user is excluded, unlike the more limited concept of ‘usability’, for example. However, experience is a very general term and so needs better definition for it to be operationalised and tested, both of which are preliminary to generalisation – the ultimate aim of HCI research. Future work should consider more exactly what is meant here by the experience, which goes beyond the ‘perception of smell’.

End Comment 4

Second, whereas earlier work states that the subjective experience of smell stimulation is crucial for the success of a system (e.g., [5]), we are unaware of work in HCI that studies the subjective experience of smell (though see [17]).

Third, several hundred receptors exist for smell and we cannot rely on any primary smells to stimulate a particular experience, as might be imagined for other human senses

Comment 5

Presumably both uses of smell here refer to what is smelled – see also Comments 1 and 2 .

End Comment 5

Taken together, these points suggest that we can only link smell tenuously to particular experiences or emotions. This limits our ability to design for a spectrum of experiences.

Comment 6

Is this not also true of other (indeed all) modalities, for example, vision and audition? The move from perception to experience and emotion seems problematic for all modalities and they may share many of the same sorts of difficulties, for example, what constitutes an experience or an emotion? How are they related? Is the relationship necessary or contingent? The difficulties corresponding to the answers to these questions should not be underestimated. See also Comment 5.

End Comment 6

The present paper focuses instead on experiences and emotions related to smell and links them to potential technologies. Inspired by work on user experience [14,34], we concentrate on personal memorable smell experiences and their links to emotion. From the focus on experience we developed design guidance for smell-enhanced technologies. The goal is to contribute knowledge on subjective smell experiences and their potential for design.

Comment 7

It would be helpful, if more could be said here about what sort of ‘knowledge’ is implicated here and in what sort of ‘design’. The latter ranges from ‘trial and error’ to ‘specify, then implement’, each with its associated support from knowledge of different sorts, as in the frameworks proposed here. The acquisition of the knowledge will vary according to the framework favoured by the researcher. Of course, all frameworks attempt to diagnose design problems and to specify design solution of users interacting with computers.

This point holds for both the current paper and any further research by others, which attempts to build on this work.

See also Comments 7, 17 and 34.

End Comment 7

We collected 439 smell stories, that is, descriptions of personal memorable experiences involving smell.We distributed a questionnaire through crowdsourcing, ensuring a large-scale coverage and variety of smell stories. We analyzed the stories and identified 10 main categories and 36 sub-categories. Each category was described with respect to its experiential and emotional characteristics and specific smell qualities. Besides smell stories associated with the past (e.g., memory of loved people, places, life events) we identify stories where smell played an important role in stimulating action, creating expectations, and supporting change (e.g., of behavior, attitude, mood). Smell can sometimes also be invasive and overwhelming, and can affect people’s interaction and communication. Within the categories, we identify common smell qualities and emotions, which support the exploration of opportunities for design. In particular, we discuss the implications for technology based on feedback from participants and on a brainstorming session with HCI researchers working on smell technologies. The main contributions of this paper are (1) an experiencefocused understanding of smell experiences grounded in a large sample of personal smell stories, which allowed us

Comment 8

Issues, concerning the meaning of ‘understanding’ are raised in Comment 3.

End Comment 8

(2) to establish a systematic categorization and description scheme for smell experiences, leading to

Comment 9

What motivates the particular categorisation and description scheme chosen? It might, for example, be ‘simply descriptive’, that is intended to characterise the phenomena described. However, the interest is, here, in and to what extent it was driven by design concerns or indeed is appropriate to address the needs of the latter – see (3). In turn, this will impact the relationship with the particular design knowledge acquired – see also Comments 7 and 17.

End Comment9

(3) the identification of technology implications by participants, and

Comment 10

See Comments 7 and 9, as concerns the research motivation with respect design and design knowledge.

End Comment 10

(4) the exploration of design potentialities by HCI

researchers.

Comment 11

See Comments 7, 9, and 10 concerning design, design knowledge and so ‘design potentialities’.

End Comment 11

THE HUMAN SENSE OF SMELL

The sense of smell is the most complex and challenging human sense.

Comment 12

This is a very strong and general claim. It could do with more justification, otherwise it seems like ‘special pleading’. The reasons, which follow are not convincing. There is not much difference between the senses, when it comes to complexity. They are certainly all complicated enough, when it comes to including them in design.

End Comment 12

Hundreds of receptors for smell exist and the mixing of the sensations, in particular with our sense of taste, is immense [2]. The sense of smell is further influenced by other senses such as vision, hearing, and touch; plays a significant role for memory and emotion; and shows strong subjective preferences. Willander and Larsson [33] showed that autobiographical memories triggered by smell were older (mostly from the first decade of life) than memories associated with verbal and visual cues (mostly from early adulthood). Moreover, smell-evoked memories are associated with stronger feelings of being brought back in time, are more emotionally loaded, and are experienced more vividly than memories elicited through other modalities [15,33]. No other sensory system makes the direct and intense contact with the neural substrates of emotion and memory, which may explain why smell-evoked memories are usually emotionally potent [15]. The emotion-eliciting effect of smell is not restricted to the context of autobiographical memories. Smell is particularly useful in inducing mood changes because they are almost always experienced clearly as either pleasant or unpleasant [8]. For instance, Alaoui-Ismaïli et al. [1] used ‘vanilla’ and ‘menthol’ smells to trigger positive emotions in their

participants (mainly happiness and surprise) and ‘methyl methacrylate’ and ‘propionic acid’ to trigger negative emotions (mainly disgust and anger). Interestingly, Herz and Engen [15] pointed out that almost all responses to smell are based on associative learning principles. They argued that only smells learned to be positive or negative can elicit the corresponding hedonic response and that people, therefore, should not have any hedonic preference for novel smells. The only exceptions are smells of irritating quality that strongly stimulate intranasal trigeminal structures. Such smells often indicate toxicity.

While neuroscientists and psychologists have established a detailed understanding of the human sense of smell, insight into the subjective characteristics of smell and related experiences is lacking.

Comment 13

See earlier Comments 3 and 8, concerning the differences between everyday day and scientific meanings of understanding.

End Comment 13

The exploration of this subjective layer of smell is often understood as going beyond the interest of these disciplines, but is highly relevant for HCI and user experience research.

Comment 14

If so, there is a need to define the supposed differences of what is lacking in scientific research, that is, ‘subjective characteristics of smell’ and ‘related experiences’. Also, is ‘going beyond’ a claim about the scope or about the level(s) of knowledge (or indeed both). Frameworks differ as to these aspects. See also Comments 1, 2, 5 and 6.

End Comment 14

SMELL IN HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION Ten years ago, Kaye [17] encouraged the HCI community to think about particular topics that need to be studied and understood about smell. While some attempts have been made to explore smell during recent years, the potential of smell in HCI remains under-explored.

Comment 15

With regards to what has the potential of smell technology remained under-explored in HCI? The current state of smell technology seems at best modest. Its potential with respect to HCI design may be likewise. At this stage, an open mind would seem to be indicated. See also Comment 12 on complexity.

End Comment 15

Most work on smell in HCI focuses on developing and evaluating smell-enhanced technologies.

Comment 16

The use of ‘enhanced’, here, is interesting, because it implies the notion of a design problem and design solution. The difference between the two is presumably ‘better’ (that is, enhanced) performance of some sort. This is, of course, important for evaluation of the enhancement, more generally in the forms embodied in different frameworks for HCI.

End Comment 16

Brewster et al. [5] used smell to elicit memories, and developed a smell-based photo-tagging tool (Olfoto). Bodnar et al. [4] showed smell to be less disruptive as a notification mechanism than visual and auditory modalities. Emsenhuber et al. [9] discussed scent marketing, highlighting the technological challenges for HCI and pervasive technologies. Ranasinghe et al. [24] further investigated the use of smell for digital communication, enabling the sharing of smell over the Internet. More examples of smell-enhanced technologies can be found in multimedia applications [13], games [16], online search interfaces [19], health and wellbeing tools (e.g., http://www.myode.org/), and ambient displays [22].

The exploration of smell-enhanced technologies is mostly limited to development efforts and the evaluation of users’ smell perception of single smell stimuli. The smells used are often arbitrary and not related to experiences. This is because of the lack of knowledge pertaining to the description and classification of smells required for HCI [17]. Kaye points out that “There are specific ones [classification and description schemes] for the perfume, wine and beer industries, for example, but these do not apply to the wide range of smells that we might want to use in a user interface” (p. 653). Thus, previous work has a general and quite simple usage of smell.

Comment 17

It would be interesting to know if, and how, this work has been or might be built on by other researchers. Was it of influence in the present case? See also Comments 7, 9, 10, and 11, concerning design.

End Comment 17

THE POTENTIAL OF STUDYING SMELL EXPERIENCES

In contrast to the work reported above, the present paper focuses instead on experiences with smell and links them to potential technologies. We do so through stories of experiences with smell. Stories are increasingly used within user experience research to explore personal memories of past experiences, but also to facilitate communication in a design process [3,34]. Stories are concrete accounts of particular people and events, in specific situations [10],

Comment 18

Stories may be ‘concrete’; but they are also abstract, in the sense that they very often (maybe always) have meaning. Without the latter at all, they are hardly ‘stories’ (although they may be sensory experiences). The truth of the stories is, of course, here unvalidated, as are the memories at the time of perception and the reports of the memories, at the time of recall. This uncertainty needs to be carried forward into the research in some way and especially as concerns the conclusions. Otherwise, the reader may be misled as to the actual state of affairs described and the description itself. When participants make claims about the relationship between a smell and an emotion, the claim is a (subjective) description (and no more or less). There is no corroborative evidence of the claim. This is critical for the type of framework, appropriate for this case. See also Concluding Comment.

End Comment 18

and are more likely to stimulate empathy and inspire design thinking than, for example, scenarios.

Comment 19

This is a strong claim and needs more justification, than that given here. Also, scenarios and histories both have their own strengths and weaknesses. Were scenarios seriously considered, as a means for conducting the data gathering?

End Comment 19

STUDY METHOD

We asked a large sample of participants to report smell experiences that were personal and meaningful.

Comment 20

See Comment 18, concerning the concrete and abstract aspects of stories with respect to their meaningfulness. Also the Concluding Comment.

End Comment 20

We refer to the description of these experiences as smell stories. These stories were captured through a questionnaire described below, which included inspirational examples of smell-enhanced technologies at its end. Based on the examples we asked participants to reflect on their experience and future technologies. The rationale of this approach was to begin from smell experiences that matter to participants, instead of starting from an application or a particular technology.

Comment 21

The rationale is good, as far as it goes; but does not address the issues raised in Comment 18. The latter must, at least be taken as qualifications of some sort, especially as concerns the conclusions. See also Concluding Comment.

End Comment 21

Questionnaire

We created a web-based questionnaire consisting of six parts. We started with an open question to stimulate the report of a personal memorable smell experience. This was followed by closed questions aiming to elucidate the relevant emotional and experiential characteristics, as well as the smell qualities. Participants could freely choose the story to report. The questionnaire was administered through a crowdsourcing platform to obtain a large sample of smell stories. Crowdsourcing provides valid and reliable data [20] and has been used for capturing user experiences [31].

Comment 22

This is a very general rationale and is acceptable as such; but it also needs particular tailoring to the present case, in order to show how the information obtained is of the kind sought and why we might have confidence in the latter relationship. See also Comments 18, 21 and the Concluding Comment.

End Comment 22

Part 1: Smell Story

The smell stories were elicited through an initial exercise, where participants were asked to think about situations and experiences where smell played an important role. The aim was to get participants into the right frame of mind and sensitize them to smell. Next, participants were asked to describe one memorable smell experience in as much detail as possible, inspired by the questioning approach used in explicitation interviews [23]. This questioning technique is used to reconstruct a particular moment and aims to place a person back in a situation to relive and recount it. Part 1 of the survey was introduced as follows: Bring to your mind one particular memorable moment of a personal smell experience. The experience can be negative or positive. Please try to describe this particular smell experience in as much detail as possible. You can use as many sentences as you like, so we can easily understand why this moment is a memorable experience involving smell for you.

Participants were asked to give a title to their story (reflecting its meaning) and indicate if the experience was positive, negative, or ambivalent (i.e., equally positive and negative). They were also asked to indicate how personally relevant the experience was (from ‘not personally relevant at all’ to ‘very personally relevant’).

Comment 23

Again, it would useful to have the rationale, which relates these questions to the knowledge that the research intended to acquire. See alo Comments 7, 9, 10, 11 and 16.

End Comment 23

Part 2: Context

Part 2 asked participants to give further details of their reported experience via open and closed follow-up questions. There were four questions on the context of the described experience, including the social context (who else was present), the place (based on the categories used by [26]), the location (as an open field), and the time when the reported experience took place (days, weeks, months, or years ago).

Comment 24

As noted earlier (Comments 18 and 21 ), the correctness/truth of the responses, here, cannot be checked or indeed corroborated or in any other way cross-referenced. Any conclusions need to reflect these concerns, for example, by way of caution. See also Concluding Comment.

End Comment 24

Part 3: The smell

Specific questions on the characteristics and qualities of the smell were asked in Part 3. Participants characterized the smell itself using a list of 72 adjectives (i.e., affective and qualitative terms) derived from the ‘Geneva Emotion and Odor Scale’ (GEOS) [7]. Participants could also add descriptions to characterize the smell in an open feedback box. In addition, they rated the smell with respect to its perceived pleasantness, intensity, and familiarity.

Part 4: Experienced emotions

In Part 4 participants had to describe how they felt about the experience as a whole, using a list of affective terms (101 in total). They could go through the list and tick the words that best described their emotions during the experience. The words were derived from Scherer [27]. Participants could also add their own words in a free-text field.

Part 5: Smell technologies

After the participants had selected, thought about, and described a particular smell episode, Part 5 linked their personal experience to technology. The participants were engaged in a envisioning exercise inspired by work on mental time travel [30]. They were shown six inspirational examples of smell technologies, namely: Olfoto: searching and tagging pictures (CHI, [5]); Smelling screen: ambient displays (IEEE, [22]); Digital smell: Sharing smell over the Web (ICST, [24]); Scent dress: interactive fabric with smell stimulation (http://www.smartsecondskin.com/); Mobile smell App: iPhone To Detect Bad Breath and Other Smells (BusinessInsider 01/2013), and Smell-enhanced cinema: Iron Man 3 Smell-Enhanced Screening (Wired 04/2013). These six technologies cover areas of relevance for HCI (mobile, ambient, wearable, personal, and entertainment computing), give realistic examples of smell technologies from research, and include recent, commercial examples.

We asked the participants to imagine any desirable change that future smell technology might make (or not) with respect to their personal smell experience.

Comment 25

Change here presumably implies enhancement and so better human (smell)-computer interactions, for example, performance of some sort. See also Comment 16. Performance, in one form or another, figures in all the frameworks, proposed here.

End Comment 25

We asked them the following questions:

(1) How could your experience be enhanced?

(2) What technology are you thinking about?

(3) Why would such a combination of your experience and the technology be desirable, or why would it not?

Comment 26

Again, ‘desirable’ invokes the idea of enhancement and performance and can be linked to the notion of design solution (and so design problem). See also Comments 7, 9, 10, 16 and 25. The issue is important, as it is central to evaluation of smell technology designs and so to all types of framework.

End Comment 26

Finally, the participants could express any other ideas for smell technology in a free-text field.

Part 6: Personal background

At the end of the questionnaire, participants answered questions on their socio-demographic and cultural background. The goal was to try to identify any geographical and cultural influences on smell attitudes (as found by Seo et al. [29]). The participants were also asked to assess their own smell sensitivity. All the questions, except for those on demographics, were mandatory. On average, the survey took 16 minutes to complete (SD = 7.57 minutes). Participants received US$ 1.50 for completing the questionnaire, corresponding to an hourly salary of 5.63 dollars.

Comment 27

It may surprise some, how short a time participants took to complete the questionnaire. Were they researchers too? If so, any particular reason or additional comment?

End Comment 27

Collected data and participants

A total of 554 participants began the questionnaire. Of these, 480 completed the questionnaire and answered three verification questions at its end. These questions required participants to describe the purpose of the study without being able to go back and look at the earlier questions or guidelines. After data cleaning, 41 stories were excluded. Fake entries (n = 11) were identified immediately, while repeated entries (n = 10), incomplete stories (unfinished sentences; n = 6), and incomprehensible stories (which did not make sense on their own; n = 14), were excluded iteratively throughout the coding process. This left us with 439 smell stories.

Comment 28

Is this par for the course? Is it about what was expected? Are there any implications for the conclusions?

End Comment 28

At the time of the study, all 439 participants (52.8% female) lived in the US; most had grown up in the US (95%). The participants’ age ranged from 18 to 67 years (M = 31.5, SD = 10.0). A majority of participants (84%) indicated being sensitive to smell (rating 4 or higher on a scale from 1 to 5).

Data analysis

The analysis process followed an open and exploratory coding approach [25]. Two researchers conducted the qualitative coding process. After coding an initial 25% of the stories, two more coding rounds (to reach 33% and then 50% of the data), led to the establishment of an agreed coding scheme. The coding scheme contained 10 main categories and 36 sub-categories, and a category entitled ‘not meaningful’ for cases where smell did not seem to have any relevance in the described experience. Based on this coding scheme, one researcher coded the remaining 50% of the data, and the second researcher coded a subsample of 25% of that data, resulting in a good inter-coder agreement (Cohen’s kappa of κ = .68) [12].

Comment 28

But as expected? Good enough (for what)? An additional comment would be informative here.

End Comment 28

Follow up design brainstorming

In addition to the feedback from our participants,

Comment 29

‘Feedback’ seems an odd choice of term to use here. Do you have any particular meaning in mind? Otherwise, ‘responses’ or ‘information’ might be better, since more neutral. It would stop the reader from unnecessarily looking for inappropriate, additional meanings, if none are intended.

End Comment 29

we also explored the design value of the smell stories with experts in the field. We organized a two-hour design brainstorming session with three HCI researchers, two working on smell technologies and one working on advanced interface and hardware design. None of them were from the same organization as the authors and none were familiar with the details of the study before the session.

The brainstorming session aimed to share and interpret the smell stories and followed four stages [11]: (1) prompting, (2) sharing, (3) selecting, and (4) committing. We selected 36 stories (one representative story for each sub category) as brainstorming prompts. All 36 stories were printed on A6 sheets (including the story title, the smell story, context information, and personal background). Each researcher was asked to read through the stories individually before discussing them together. They were asked the same questions as our participants (e.g., how they might imagine a connection between the experience and technology). Each researcher chose the most interesting/inspiring stories to share with the group, then they generated ideas as a group, and selected three to four ideas to be developed in more detail. The outcome of the brainstorming session is presented in the implication section, after the description of the findings from the smell stories.

Comment 30

This is an interesting method structure; but it would be helpful to have more rationale for the decisions taken. It is also essential to provide examples of the data for the reader to appreciate the smell stories and the brainstorming data, as you do later in the paper. After trying to answer the questions myself given to both groups, I feel more confident, as to the form of the actual data collected, after reading the examples.

End Comment 30

FINDINGS ON EXPERIENCES WITH SMELL

In the following sections we present our findings according to the 10 identified categories. The 439 smell stories were organized via their primary category, as agreed by the coders. This categorization does not define a strict line between the categories, as they are not wholly independent, but it does enable us to organize the material and generate a useful dataset for design.

Comment 31

Add criteria, here, for this claim. See also Comments 7, 9, 10, and 23.

End Comment 31

Below we provide for each category a rich description of the particularities of the stories, excerpts from example stories, and their associated smell qualities and emotions. Each category also contains information about the participants’ own rating of the stories as positive, negative, or ambivalent.

Category 1: Associating the past with a smell

This category is the largest and contains 157 stories. In these stories, the participants described a past experience in which a smell was encountered during a special event in life (e.g., ‘Wedding Day’, ‘New House’), at a special location (e.g., ‘The Smells of Paris’, ‘Grandma’s House’), or as part of a tradition (e.g., ‘The Smell of Thanksgiving’ or ‘Christmas Eve’). In these stories the smell was described as having a strong association to those particular moments in the past, with no actual smell stimulus in the present. A particularity of this category is the distinction between stories describing personal memorable events versus personal life events (e.g., ‘Disneyland’ versus ‘When my mother died’). Smells were also associated with personal achievement/success (e.g., ‘Scent of Published Book’, ‘New Car Smell’) and other important episodes of change, such as “‘Fresh Start’: I was taking a job in a new city. …. I took a plane trip across the country and the moment I took a step off the plane and took a deep breath will always stick with me. It felt so clean and the air actually smelled fresh and new” [#488]. Within this story, the qualities of the smell were for instance described as fresh, energetic, and invigorating. Some of the emotions experienced at this moment were courageousness and excitement. Although this category is dominated by positive experiences (n = 127), negative experiences were also reported (n = 27), such as ‘Car Crash’.

Category 2: Remembering through a smell

The 40 stories in this category described a recent experience of a smell, which reminded participants about past events, people, locations, or specific times in their life. In contrast to the previous category (where stories describe a direct link from the recollected past smell to the present; e.g., the smell of ‘Grandma’s House’), this category contains stories that describe an indirect link from the present experienced smell stimulus

Comment 32

‘Smell stimulus’ meaning is very clear here. See also Comments 1, 2, and 5 .

End Comment 32

to the past event, person or place (e.g., the smell of chocolate cookies as sudden reminder about grandma). Most stories in this category contain reminders of childhood described as ‘sweet’, ‘reassuring’ and ‘nostalgic’ with respect to the qualities of the smell. A sub-set of stories in this category (n = 10) also highlight the particular power of smells to take a person back in time. The description of such a flashback caused by a sudden smell stimulus was described as: “‘My first love’: It was the next day, when I was walking through the local Macy’s that I smelled something that threw me back into that situation, I could feel and see everything that had happened the day before when I smelled a perfume in the store” [#630]. Some of the qualities used to describe the smell were attractive, erotic, and fresh. The experienced emotions were described as amorous, aroused, excited, hopeful, and interested. The stories in this category were mainly positive (n = 37), except for three.

Comment 33

It would be useful somewhere to provide the criteria, by which a description was characterised as an ’emotion’. The latter is notoriously difficult to pin down. See also Comments 18 and 21.

End Comment 33

Category 3: Smell perceived as stimulating

The 62 stories in this category described experiences with a unique, mostly unknown smell (all stories, except one, were positive). The smells arose from different sources, such as perfume, food, and nature. A particularity of this category is the quality of ‘first time’ encounters with a smell across all origins. One participant described the first time he was at a beach: “The smell was very different from anything I had ever experienced before. At first I was kind of grossed out by the smell, but I grew to love it” [#921]. Another participant described the smell of a tornado experienced for the first time: “It was similar to the smell before rain but had a certain sharpness to it, as if to warn of the incoming danger. I felt like I knew this smell but at the same time, it felt foreign to me. It wasn’t a bad smell, it was just slightly unfamiliar” [#713]. The smell qualities and experienced emotions were often described with mixed attributes (e.g., heavy, imitating, and stimulating; attentive, serious, and calm), but still rated as positive experiences by participants. Most of the other stories in this category reported on the first experiences with food (e.g., ‘Slice of Heaven’) and nature (e.g., ‘Grass’), and were described as desirable, fresh, or pure, and provoked feelings of happiness at the moment they occurred. Although specific memories were established, including unique new associations (e.g., ‘Tornado smell’), the stories in this category did not evoke the kind of strong connections to the past as described in Category 1 and 2.

Category 4: Smell creating desire for more

This category contains 48 stories (45 positive). Key to these stories is that the smell grabbed the persons’ attention unexpectedly. The smell was either associated with food (triggering appetite), nature (triggering curiosity), or the scent of other people (triggering attractiveness), which motivated one to do or get something. In some stories smell was described in relation to the sensation of newness (e.g.,‘The sweet smell of CPU’: …There was the smell of the cardboard boxes it all arrived in, the smell of new metal– perhaps it was a combination of these and other things, but when the building was complete there was just a singular smell that was unique to a new computer built by my own hands” [#685]). The qualities of the smell in this story included beneficial, heavy, sophisticated, energetic, and pleasantly surprising. The experienced excitement was expressed through words such as confident, delighted, enthusiastic, impressed, or triumphant. This category also contained one story where the smell at a funeral stimulated reflection in the moment (e.g., ‘The scent of moving on’). The story was rated as a positive experience and at the same time the smell was described as clean, penetrating, and persistent, and the participant indicated that she was afraid, anxious, discontented, sad, tired, and uncomfortable. Despite the negative situation described in this story, the smell gave hope and a desire to live and move on, looking into the future in contrast to the stories in Category 1 and 2.

Category 5: Smell allowing identification and detection